Introduction to Adolescent Sleep Patterns

Sleep is foundational to human health, especially during adolescence—a period of rapid physical, emotional, and cognitive development. Yet, many parents find themselves locked in nightly battles with their teens over bedtime. The conventional view often attributes these late-night habits to defiance or laziness. However, scientific research reveals a complex interplay of biological and developmental factors driving teenagers’ late-night tendencies.

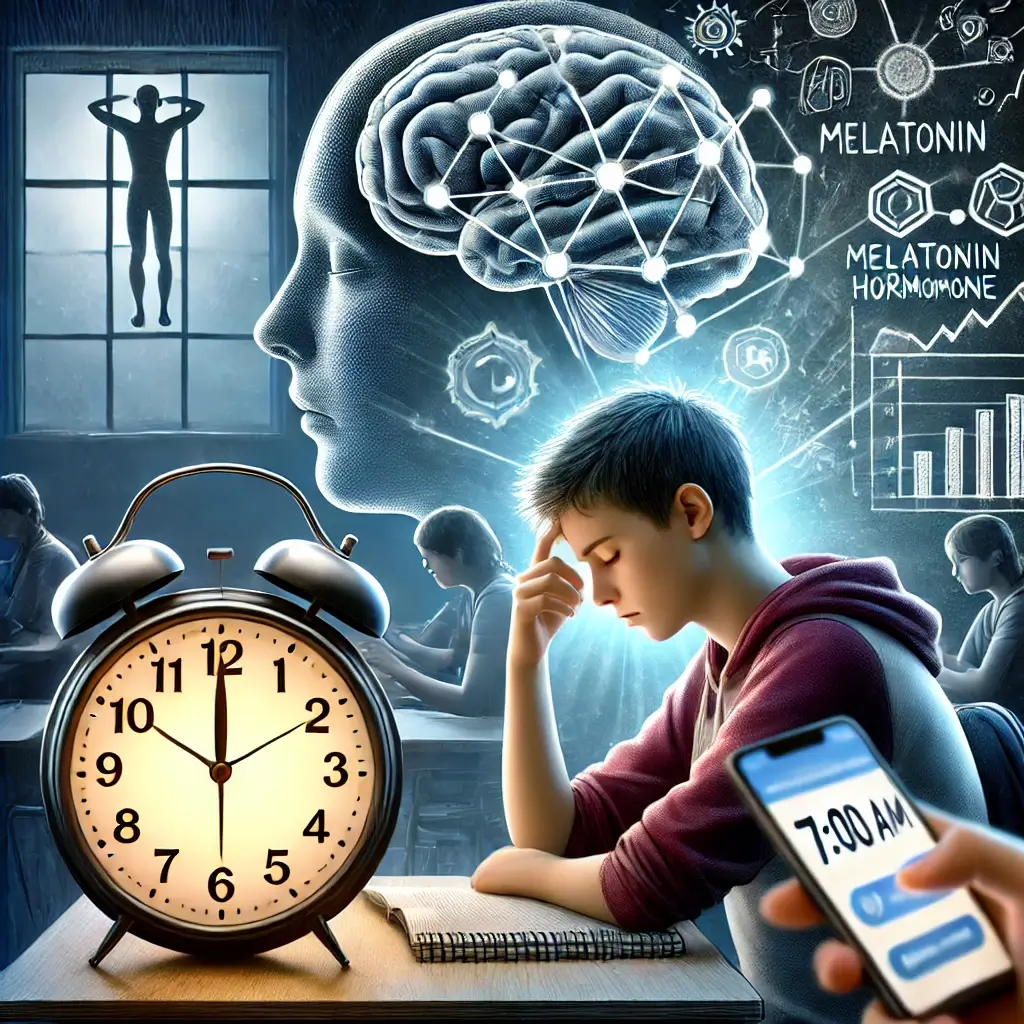

During puberty, the adolescent brain undergoes significant changes, including shifts in the circadian rhythm and delayed melatonin production, and ongoing prefrontal cortex development, all of which contribute to later sleep onset. Compounding these biological factors are societal pressures such as early school start times, extracurricular activities, and increasing engagement with digital technology. These factors collectively create a perfect storm that results in chronic sleep deprivation, with far-reaching consequences for teenagers’ physical health, mental well-being, and academic performance.

Scientific Background of Teen Sleep

This article explores the science behind adolescent sleep patterns, the risks of sleep deprivation, and strategies to help teenagers achieve healthier sleep habits, emphasizing the need for empathy and evidence-based solutions.

Understanding Circadian Rhythm Changes

A defining feature of puberty is a delay in the natural sleep-wake cycle, known as a “sleep phase delay.” Melatonin, the hormone responsible for inducing sleep, begins to be released later in the evening, pushing bedtime back by 1–2 hours compared to pre-adolescent children (Carskadon et al., 2004). This shift means that teenagers feel sleepy later at night and naturally wake up later in the morning. However, early school start times and sleep debt force teenagers to wake up before their bodies are biologically ready, leading to cumulative fatigue.

Brain Development and Sleep

The adolescent brain is in a state of heightened plasticity and prefrontal cortex development, with the prefrontal cortex, which governs decision-making and impulse control, still developing (Blakemore & Robbins, 2012). This immaturity can make it harder for teenagers to prioritize long-term health benefits, such as adequate sleep, over immediate rewards, such as socializing or gaming.

Social and Technological Impacts

Social interactions are a cornerstone of adolescent life. Many teenagers use late-night hours to connect with peers via social media and digital entertainment platforms. While these activities fulfill their developmental need for connection, they also expose teens to artificial light, which suppresses melatonin production and disrupts circadian rhythms (Chang et al., 2015).

Effects of Sleep Deprivation

Sleep deprivation during adolescence can have profound consequences, affecting cognitive, emotional, and physical health outcomes.

Academic Performance Impact

Sleep is essential for memory consolidation and cognitive processing. A 2015 study published in Sleep Health found that high school students with insufficient sleep duration had significantly lower academic performance than their peers who met the recommended sleep duration (Wheaton et al., 2015).

Mental Health Implications

Adolescents who consistently lack sleep are at greater risk of depression, anxiety, and mood swings. A 2018 study in the Journal of Youth and Adolescence revealed a strong correlation between sleep deprivation and mental health symptoms in teens (Beattie et al., 2018). This underscores the role of sleep in maintaining emotional stability during a time of heightened vulnerability.

Physical Health Consequences

Sleep deprivation has been linked to a weakened immune system and increased metabolic disorders. Inadequate sleep also exacerbates impulsive behavior, increasing the likelihood of risky activities such as drowsy driving—a leading cause of motor vehicle accidents among teenagers (CDC, 2021).

Solutions for Better Sleep

Despite the biological and societal challenges, several strategies can help teenagers establish better sleep routines.

Schedule Adjustment Strategies

Encourage teens to gradually shift their sleep schedules by 15–30 minutes weekly sleep schedule adjustments, aligning their bedtime closer to the desired schedule.

Sleep Environment Optimization

Promote a consistent bedtime routine and optimal sleep environment, limit screen time an hour before bed, and create a dark, quiet sleep environment to support natural melatonin production.

Policy and Environmental Changes

Support initiatives for later school start times. Studies show that delaying school start times improves student performance can significantly improve students’ sleep duration and academic outcomes (Wheaton et al., 2016).

Natural Light Exposure

Encourage teens to get morning sunlight exposure for circadian rhythm regulation within an hour of waking to help reset their circadian rhythm and promote earlier sleep onset.

Final Thoughts on Teen Sleep Patterns

Teenagers’ late-night tendencies are not merely a matter of poor discipline; they reflect deeply ingrained biological and developmental processes. Understanding the science behind these behaviors can foster empathy among parents and educators, paving the way for more supportive and effective interventions. By combining evidence-based sleep improvement strategies, families and communities can help teens overcome the challenges of sleep deprivation. A proactive, science-informed approach ensures that teenagers are better equipped to thrive academically, emotionally, and physically.

References

Beattie, L., Kyle, S. D., Espie, C. A., & Biello, S. M. (2018). Social interactions, emotion, and sleep: A systematic review and research agenda. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 37, 83–97.

Blakemore, S. J., & Robbins, T. W. (2012). Decision-making in adolescence. Nature Neuroscience, 15(9), 1184–1191.

Carskadon, M. A., Acebo, C., & Jenni, O. G. (2004). Regulation of adolescent sleep: Implications for behavior. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1021, 276–291.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). High school start times for students. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov

Wheaton, A. G., Ferro, G. A., & Croft, J. B. (2015). School start times for middle school and high school students—United States, 2011–12 school year. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64(25), 809–813.